A Guide to 25 Waterfalls from Canal to Coast and points between

Receiving hundreds of inches of rain annually, the Hoh, Quinault and Queets Rainforests are located on the coastal foothills of the Olympics, receiving 21+’ of snow and rain at its peaks! It’s no wonder there is a myriad of spectacular waterfalls lacing the area. Explore this sampling curated by celebrated guidebook author and avid hiker, Craig Romano. Some are small, secret, and unique, others are popular but magnificent. All are worth the journey!

When Craig Romano agreed to share with us a few of his favorite waterfalls in the Pacific Coastal region of Washington, we were frankly thrilled. If you’re looking for straight details on Northwest hikes and wilderness destinations — and fun facts - Craig is the guy to call.

Craig has written more than 20 hiking guidebooks including Day Hiking Olympic Peninsula 2nd Edition which includes details for popular and little known hikes across the Peninsula. An avid hiker, runner, paddler, and cyclist, Craig is currently working on Urban Trails Vancouver USA (2020); Backpacking Washington 2nd Edition (2021); and Day Hiking Central Cascades 2nd Edition (2022). He is also a featured columnist for the Fjord and Explore Hood Canal.

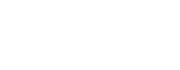

Enchanted Valley | Craig Romano photo

Why we are so keen about our falls?

As storms from the Pacific Ocean move across the peninsula, they crash into the Olympics and are forced to release moisture in the impact. Consequentially, the clouds release massive amounts of moisture (up to 170 inches annually) in the coastal side of the range – creating the “rain shadow effect.”

The massive rainfall has given life blood to the hanging mosses of the perpetually wet Northwest rainforests – Hoh and Quinault. On top the Olympic Mountains this moisture lands as snow frosting the peaks with as much as 35 feet each year.

Each spring the snow melts and creates icy run-off. Mix in a little more rainfall and the result is a spectacular waterfalls ring envelops the base of Olympic range.

Pacific coastal waterfalls are gorgeous year round but tend to be most spectacular in early spring or during the autumn rainy season.

Let’s go Chasing Waterfalls

1. Tumwater Falls

Olympia Metro | Located minutes from Olympia, Tumwater Falls is an iconic landmark near the state capital. These thundering multi-tiered showy falls along the Deschutes River are located within a 15-acre park created on land donated by the Olympia Brewing Company. Meander along manicured paths and saunter over foot bridges and under historic road bridges taking in a little history along with the sensational scenery.

At the base of the upper falls admire a replica of the famous bridge that once appeared on the labels of Olympia beer spanning the river above the lower falls. Walk trails along the gorge between the falls and admire deep pools, eddies and jumbled boulders. Take time to read the informative panels on Tumwater—Washington’s oldest permanent non-Native settlement on Puget Sound. Let’s Go!

2. Kennedy Creek Falls

Kamilche, South of Shelton | From its origin at Summit Lake in the Black Hills, Kennedy Creek flows just shy of 10 miles to Oyster Bay tumbling over a two-tiered waterfall along the way. Reaching these pretty falls involves a half day hike on a closed-to-vehicles logging road through patches of cuts and mature standing timber. Start walking across a recent cut. In about a mile reach a grove of mature timber and the Kennedy Creek Salmon Trail which opens in the fall for salmon viewing and field trips. Keep walking on the main road avoiding diverting roads. The route leaves state land for private timberland and rolls along. Take in decent views of the surrounding foothills. At 2.8 miles (just before crossing a creek) follow an obvious but unmarked trail to the right. This path can be muddy and slick during periods of heavy rainfall. The trail descends to a grove of big cedars, firs and yews—and the falls. Here Kennedy Creek tumbles over an ancient basalt flow. The upper falls are small but quite pretty. The lower falls are difficult to see as they tumble into a narrow chasm of columnar basalt. Let’s Go!

3. Vincent Creek Falls

South Hood Canal, Skokomish Valley | While Vincent Creek Falls are quite stunning crashing 250 feet into the South Fork Skokomish River in a deep narrow canyon; the High Steel Bridge which allows for their viewing is even more spectacular. The 685-foot long bridge spans 375 feet above the canyon. Walk across the bridge but use caution along its north side where the guardrail is only 3 feet tall. The arched truss steel bridge was built in 1929 originally for a logging railroad. In 1950 it was converted for road use. It is the 14th highest bridge in the country. Your heart is sure to pound as you walk upon its airy span. Eventually Vincent Creek Falls comes into view. Through a series of falls, Vincent Creek drops 250 feet down a canyon wall into the roaring South Fork Skokomish River. Walk all the way across the bridge if you plan on capturing the falls in their entirety in a photo. Let’s Go!

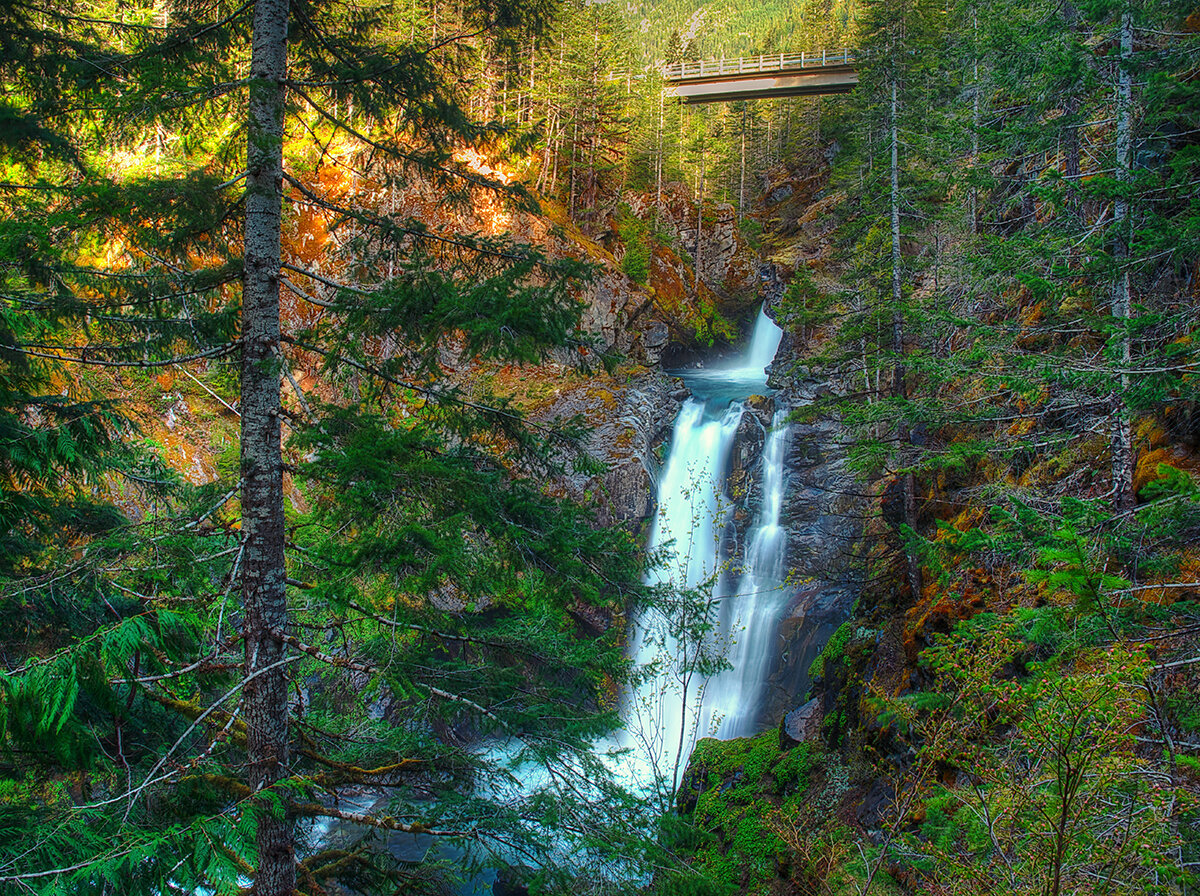

Big Creek | Craig Romano Photo

4. Big Creek Cascades

Lake Cushman Area, Hood Canal | Amble on a circuitous route in the Big Creek drainage within the shadows of Mount Ellinor; and delight in a series of small tumbling cascades. This wonderful loop utilizes old logging roads, new trails and a series of beautifully built bridges. It was constructed by an all-volunteer crew that continues to improve and maintain this excellent family and dog-friendly loop. Starting from the Big Creek Campground, follow the Upper Big Creek Loop Trail to Big Creek and the first of several sturdy bridges along the way. After a short climb you’ll reach the Creek Confluence Trail which drops to the confluence of the tumbling Big and North Branch Creeks. The main loop continues to cross North Branch Creek on a good bridge. Just beyond it crosses Big Creek on a new bridge above a gorgeous cascade. The loop then descends skirting big boulders and passing good views of roaring Big Creek. It crosses a couple more cascading creeks before traversing attractive forest and returning to the campground. Let’s Go!

5. Staircase Rapids

Lake Cushman Area, Hood Canal — Currently Closed until mid-September

This loop involves a section of an historic route across the Olympic Mountains to a suspension bridge spanning the North Fork Skokomish River near a series of thundering rapids. Cross the North Fork Skokomish on a solid bridge and follow a trail that was once part of the original O’Neil Mule Trail. In 1890 Lieutenant Joseph O’Neil accompanied by a group of scientists led an Army expedition across the Olympic Peninsula. Among his party’s many findings was a realization that this wild area deserved to be protected as a national park. March up alongside the roiling river, passing big boulders and a series of roaring rapids. The rapids’ name come from a cedar staircase O’Neil built over a rocky bluff to get past them. Follow the bellowing river from one mesmerizing spot to another before reaching a sturdy suspension bridge spanning the wild waterway. Cross the river and complete this delightful loop by now heading downriver following the North Fork Skokomish River Trail back to the Ranger Station. Let’s Go!

Hamma Hamma | George Stenberg photo

6. Hamma Hamma Falls

Hamma Hamma River Valley, Hood Canal | Talk about a bridge over troubled waters. From the Mildred Lakes Trailhead walk across the high concrete bridge at the road’s end. You no doubt heard the roar of the falls when you drove across it. Now peer over the bridge and witness the cataracts responsible for the racket.

Directly below, the Hamma Hamma River careens through a tight rocky chasm. These impressive falls are two-tiered crashing more than 80 vertical feet. The road spans directly above the upper and smaller of the falls. The overhead view is pretty decent, but the lower and larger falls are more difficult to fully see. A very rudimentary path leads along cliff edges for better viewing, but it’s slick, exposed and treacherous.It’s best to experience the falls from the safety of the bridge. During periods of high water flow you’ll get the added bonus of feeling the falls too thanks to a rising mist. On the drive back look for a couple of pull-offs providing views of secondary falls along the Hamma Hamma, Let’s Go!

7. Murhut Falls

Duckabush River Valley, Hood Canal | Hidden in a lush narrow ravine and once accessed by a treacherous path, Murhut Falls were long unknown to many in the outside world. But now a well-built trail allows hikers of all ages and abilities to admire this beautiful 130-foot two-tiered waterfall. The trail starts by following an old well-graded logging road. It was past logging in this area that led to the discovery of these falls. The old road ends after a short climb of about 250 feet to a low ridge. The trail then continues on a good single track slightly descending into a damp, dark, cedar-lined ravine. As you work your way toward the falls, its roar will signal you’re getting closer. Reach the trail’s end and behold the impressive falls crashing before you. The upper falls drops more than 100 feet while the lower one crashes about 30 feet. Blossoming Pacific rhododendrons lining the trail in May and June make the hike even more delightful. Let’s Go!

Rocky Brook Falls

8. Rocky Brook Falls

Dosewallips River Valley, Hood Canal | One of the tallest waterfalls on the Peninsula, Rocky Brook Falls is also among the prettiest. Follow the trail past a small hydroelectric generating building and come to the base of the stunning towering falls fanning over ledges into a large splash pool surrounded by boulders. This classic horsetail waterfall crashes more than 200 feet from a small hanging valley above. While a penstock diverts water from the brook for electricity production, the flow over the falls is almost always pretty strong. Like all waterfalls, these too are especially impressive during periods of heavy rainfall. On warm summer days the falls become a popular destination for folks seeking some heat relief. And while many waterways east of the Mississippi River are called brooks, creek is the preferred name in the west. There are only a few waterways on the Peninsula called brooks, and they were more than likely named by someone who hailed from back east. Let’s Go!

9. Dosewallips Falls

Dosewallips River Valley, Hood Canal | This spectacular waterfall used to be easily reached by vehicle. But the upper Dosewallips Road has been closed to vehicles since 2002 after winter storms created a huge washout that has yet to be repaired. Now to reach this waterfall you must hike or mountain bike the closed road. Walk past the road barrier and immediately come to the washout and a bypass trail. Steeply climb on the riverbank above the slide. Then descend back to the road and walk along the churning river. The road then pulls away from the river, passes a campground and climbs. The river now far below in a canyon is out of sight, but not out of sound. Pass beneath ledges and cross cascading Bull Elk Creek on a bridge. At 3.9 miles in a recent burn zone enter Olympic National Park. Cross tumbling Constance Creek on a bridge and continue climbing passing a big overhanging boulder. Then descend and skirt beneath a big ledge coming to the base of dramatic 100-foot plus Dosewallips Falls. Admire the raging cascade’s hydrological force—it’s mesmerizing. Let’s Go!

10. Fallsview Falls

Big Quilcene River Valley | As far as cascades go, Fallsview Falls lacks the “Wow factor.” However the canyon these falls tumble into is pretty impressive. And if you plan your visit for late spring, blossoming rhododendrons line the trail and frame the view with brilliant pinks and purples. The trail to the falls is short, easy and ADA accessible. Follow the 0.2 mile loop to a fenced promontory above a tight canyon embracing the Big Quilcene River. Gaze straight down to the roiling river. Then cast your glance directly across the canyon to an unnamed creek cascading 100 feet into it. By late summer it just trickles—but during the rainy season the falls put on a little show. If you want to stretch your legs some more afterward, you can follow a trail into the little canyon and hike along the frothing river. Let’s Go!

And 15 more…

For a day trip, weekend, or a month-long adventure – the Olympic Peninsula is a fantastic place to get away and enjoy nature – and waterfalls! It’s not just 1000’s of waterfalls, there are countless lakes, rivers, streams and trails to suit every ability level. Embraced by the Pacific Ocean on the west, the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the north, and the Hood Canal on the east, it is famed for being home to Olympic National Park, more than 600 miles of hiking trails and 73 miles of pristine ocean wilderness beaches.

The Olympic Peninsula hosts activities for families and outdoor enthusiasts alike, attracting visitors from near and far. Start planning your next adventure!

Click here for a complete list of all 25 waterfalls on the Olympic Peninsula curated by Craig!

Crossing the Bar - McMicken Island

There are no bridges or causeways to little McMicken Island in Case Inlet. No ferry service either. But you don’t need a kayak or boat to visit. You can easily hike to this island which lies about 0.2 mile off of the eastern shore of Harstine Island. It’s all in the timing.

Craig Romano | Story & images

There are no bridges or causeways to little McMicken Island in Case Inlet. No ferry service either. But you don’t need a kayak or boat to visit. You can easily hike to this island which lies about 0.2 mile off of the eastern shore of Harstine Island. It’s all in the timing.

When the tide is low, a tombolo (a sandbar connecting the island to the mainland—or in this case another island) is exposed allowing you dry foot access to the island. You then can hike the island’s small half mile trail, picnic in its small meadow, or explore big barnacle-encrusted rocks in its intertidal zone. Just mind the incoming tide lest you make a big splash on your island exodus.

Hit the Trail

The hike to little 11.5 acre McMicken Island begins from the 300-acre Harstine Island State Park. A former Washington DNR property, most of the old timber was logged off, but small groves of old-growth remains on the property.

You want to head to the park’s beach reachable by the two trails taking off south from the parking lot. Take the one on the eastern end of the lot (away from the kiosk) for the more direct route.

The trail heads towards Case Inlet soon reaching the edge of a 100 foot high forested bluff. Continue along the bluff taking in glimpses of the remote beach below. The way then descends into a cool and dark ravine graced with big cedars and firs and reaches a junction.

The trail to the right loops back to the other main trail leaving the parking lot. Consider taking it upon your return from McMicken Island.

Head left through a row of big cedars and via a series of steps descend deeper into the ravine. After crossing a little creek the way emerges on a deserted beach. Look directly across Case Inlet to Herron Island and the Key Peninsula. Then look south and spot McMicken Island set against a backdrop of big beautiful Mount Rainier. If the tide is high, you’ll have to wait to hike the beach as overhanging trees prohibit passage. But in a low tide, a big wide easy to walk beach awaits your footprints.

Walk for more than a mile undulating between cobbles, mud and sand. Watch for sand dollars scatted across the tide flats. Look too for eagles, herons and a myriad of seabirds. Harstine is a wet place and plenty of side creeks fan out on the beach. You should be able to keep your shoes dry, but a pair of waterproof boots is not a bad idea. The entire way to the tombolo is on public tidelands. But there is a parcel of private property located between two large state park properties abutting the shoreline. Respect posted private property.

The tombolo is pretty distinctive in low tides—fairly wide and several feet raised above inlet waters. In high tides it’s completely submerged, although breakers will help you locate its position. It’s really fun to hike it when a receding tide first reveals it. Tap your inner Moses and part the seas watching the land bridge emerge as you amble along it.

Reaching the island

Once across the .2 mile sandy strip, reach McMicken Island. All of the little island except for a small fenced parcel with a couple of cabins is state park property. The private holding belongs to the family that once owned the entire island. They sold the island to the state withholding this small lot. Please keep out of it. The rest of the island however you are free to explore.

At the island’s western end is a small picnic area in a grassy opening. Here find some rare Garry oaks growing on a low bluff above the surf. Near a composting toilet at the eastern edge of the field is a small nature trail. Hike it! It weaves a half mile through towering firs and madronas to blufftop views on the eastern end of the island.

Be sure to explore the rocky tide flats surrounding the island too, and check out the large erratics scattered about. There is a particularly large one on the south side of the island. Enjoy your island wanderings and explorations—more than likely sharing it with no more than just a couple of other happy hikers. And be sure to keep track of the time and incoming tide so you don’t get trapped on the island.

Places to Stay

Waterfront cabin located on Harstine Is with beach access and a panoramic view of the Puget Sound, Mt. Rainier and McMicken island. Check availability

Hike back to Harstine Island State Park and call it a day or consider walking some more. The park contains three miles of trails. They traverse thick fir forests and swampy cedar groves and are family and dog-friendly.

McMicken Island Notes:

Forest Setting with Beach Access

Cross the bridge to Harstine Is. and enjoy a beautiful and quiet retreat in the woods. Relax in the comfortably furnished cabin or enjoy exploring the 5 acre property with meandering trails through a lovely forest. Check availability

Distance: 4.0 miles round trip

Difficulty: easy, pay attention to tides! Hike is only possible in low tides. Consult tide tables and plan accordingly. Dogs permitted on leash.

Trailhead Pass Needed: Discover Pass

GPS Waypoints: Harstine Island State Park Trailhead: N47 15.737 W122 52.236 McMicken Island Trailhead: N47 14.865 W122 51.780

Features: Kid and dog friendly, beach hiking, undeveloped coastline, small island reached via a sandbar, good bird watching, sublime views of Mount Rainier over Case Inlet.

Trailhead directions: From Olympia, head north on US 101 to Olympic Highway (SR 3) Exit in Shelton. Then turn and follow SR 3 east for 11.0 miles. Turn right onto Pickering Road (Signed for Harstine Island) and drive 3.3 miles. Then bear left onto Harstine Bridge Road and come to a T-junction upon entering Harstine Island. Go left on North Island Drive and after 3.0 miles turn right at the island community hall onto East Harstine Island Road. Proceed for one mile and turn left onto Yates Road. Continue 0.9 mile and turn right into Harstine Island State Park. Reach trailhead parking in 0.2 mile.

Wagonwheel Lake Hike features alpine views and solitude

One of the steepest trails in the Olympic Range, perhaps it's called "wagonwheel" because, as author, Craig Romano, puts it, "you’ll bust your axle" hiking this unforgiving climb if you are unprepared. Are you up for the challenge?

By Craig Romano

Craig Romano, is an author of more than twenty hiking guidebooks along with Day Hiking Olympic Peninsula 2nd Edition (Mountaineers Books), including 136 hikes on the Olympic Peninsula. craigromano.com

Utilizing tight switchbacks and no switchbacks at all, the Wagonwheel trail makes a grueling ascent up steep forested slopes. It’s a workout. There are some good, albeit limited views along the way. But you’ll probably feel short changed for the effort. In that case, summon your second wind and continue hiking heading up even steeper terrain to emerge at an unassuming peak granting sweeping views of craggy peaks, deep valleys, and some of the wildest and rugged terrain in the state.

"Old-growth forest, solitude, and alpine views await after a grueling ascent."

Hit the Trail

Sharing its start with the Staircase Rapids Loop and North Fork Skokomish River, don’t fret if the parking lot is packed. Almost all of those vehicles belong to hikers heading to those two other trails. Why not Wagonwheel Lake? Perhaps the sign at the trailhead does its job discouraging folks. It states that you’ll climb 3,200 feet in 2.9 miles followed by “Very Steep!” But even that assessment doesn’t correctly portray the magnitude of steepness of this trail.

The trail is gentle for a short stretch at the beginning and ending but still leaving nearly 2,800 feet of elevation gain within two miles. Yep—that’s very steep indeed!

Regardless of the fair warning, many hikers intent on reaching the lake ignore it or underestimate their fitness level and attempt this trail. And all too many of them poop out resigning themselves to accept that despite the trail’s short length—elevation gain can be a leveler! But for those of you who accept this hike as a challenge, take note.

The lake isn’t exactly one of the most stunning places in the Olympics. You may question if it was worth all of that sweat and toil. If your goal was a good workout in a natural environment—or perhaps a chance to commune deep in the woods all alone—then, yes it was worth it.

If it’s breathtaking views you are after, they are there, but you’re going to have to work a little bit more!

Beyond the forested basin cradling little Wagonwheel Lake you can follow a path another .4 mile and 700' of climbing to an open 4,755' knoll straddling the Mount Skokomish Wilderness-Olympic National Park Boundary.

From this spot framed with silver snags and clusters of firs you can enjoy excellent views of nearby Mount Lincoln, Mount Stone, Mount Skokomish, Mount Ellinor, Mount Washington; and the vast emerald ridges dividing the South and North Skokomish River valleys.

There are good views too across the North Fork Skokomish River Valley to Wonder Mountain, Five Ridge Peak, Six Ridge and other little known and little explored peaks. A region that pretty much looks as it did when Lieutenant Joseph P O’Neil explored this part of the Olympic interior more than 120 years ago.

Along the Way

Despite its grueling statistics, Wagonwheel Lake gets its fair share of visitors and attempted visitors. The trail starts in a lush understory of shoulder high ferns and salal.

The grade at first is deceptive, the going pretty easy. Keep a lookout to your right for an old mine shaft. Then prepare to do some serious climbing. The trail commences in a series of short tight switchbacks relentlessly ascending steep slopes.

Wind through mostly uniform seond-growth fir forest, a testament to a past disturbance—most likely a fire.

Among the monotonous make up of trees look for a few western white pines as well as Pacific rhododendrons. In late spring and early summer this flowering shrub, Washington’s state flower adds brilliant pinks and purples to the verdant surroundings. The monotony of the brutal climb however, is rarely broken.

At about 1.7 miles the trail comes to a small ledge. Here take a break and enjoy a window view of the valley below. Then commence climbing. The forest transitions from fir to hemlock. The trail and to your chagrin, steepens. Now foregoing switchbacks, the way takes an even more direct approach to subduing elevation. If you’ve hiked in the Adirondacks or White Mountains back east, the steepness of this trail compares to those areas where switchbacks are only spoken about as something that exists out west to make hiking easier.

After what feels like forever, the trail miraculously levels out. Now catch your breath, wipe your brow, swig some water and enjoy easier walking through old-growth fir and hemlock. The trail next traverses a steep slope breaking out onto a brushy avalanche chute. Work your way across slumping tread enjoying views to the northwest of Mount Lincoln and the serrated Sawtooth Range.

The trail then re-enters cool evergreen forest and crosses Wagonwheel Lake’s outlet creek. Just a hop, skip, and jump away lies the little lake in forested bowl. A small bench above the lake makes for a good place to collapse. But if you have any oomph left, locate a primitive path taking off from the main trail at the lake. It goes for a half mile straight up the 4,755-foot knoll to the north. The officially unnamed peak straddles the Olympic National Park and Mount Skokomish Wilderness in Olympic National Forest. From this peak’s meadows punctuated with silver snags enjoy a breathtaking panorama that includes the following prominent peaks: Pershing, Washington, Ellinor, Copper, Lincoln, Skokomish, Wonder, and the Brothers. Little Wagonwheel Lake sparkles below. Rest up and prepare your knees for the brutal descent.

For more trails and information check out Explore Hood Canal’s list of area hikes or visit the Explore Hood Canal Hiking Map.

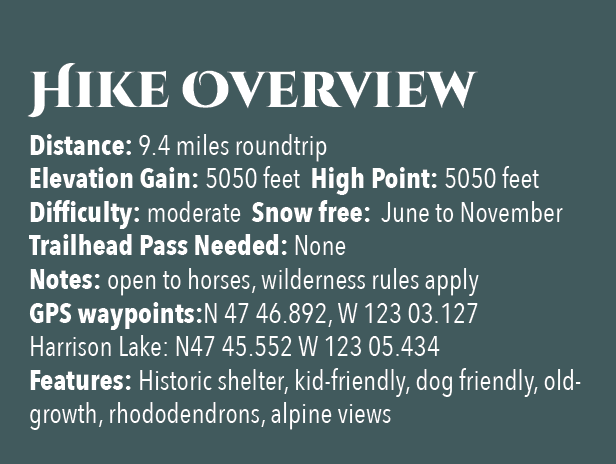

Tunnel Creek Trail Hike

Olympic National Forest’s Tunnel Creek Trail lies just a few miles south of the popular Big Quilcene Trail. But unlike the Big Quil which leads to Marmot Pass, a high windswept wildflower-rich gap providing sweeping views—the Tunnel Creek trail travels mainly beneath a thick canopy of primeval forest.

Craig Romano | author

Olympic National Forest’s Tunnel Creek Trail lies just a few miles south of the popular Big Quilcene Trail. But unlike the Big Quil which leads to Marmot Pass, a high windswept wildflower-rich gap providing sweeping views—the Tunnel Creek trail travels mainly beneath a thick canopy of primeval forest. Lacking the wow factor of Marmot Pass, Tunnel Creek gets passed over by many a hiker. However, those who take to this trail less taken soon discover; Tunnel Creek offers plenty of delightful spots and some pretty decent views as well. And all without the crowds of Marmot Pass.

Hit the Trail

The Tunnel Creek Trail immediately enters the 44,258-acre Buckhorn Wilderness, the largest roadless area in Olympic National Forest. Much of the wilderness lies within the Olympic rain shadow encompassing some of the driest mountainous terrain in the Olympics. But here at the wilderness’s southern reaches, precipitation increases. And it’s noticeable immediately upon starting up the trail. The surroundings are verdant—draped in mosses and lichens. The trees are grand. And the valley is alive with the sound of cascading water.

Work your way up a tight valley following alongside tumbling South Fork Tunnel Creek through a tunnel of towering old-growth western hemlocks and Douglas-fir. The hike is magical, almost ethereal on a misty morning. And it’s welcoming on a sweltering summer day, as the ancient trees do an excellent job of regulating the temperature, providing some much appreciated air-conditioning.

After 3.3 miles and gaining a modest 1500 feet of elevation, reach the still intact Tunnel Creek Shelter. A remnant from when this trail was much longer (before logging and roads obliterated much of it). In the early days of Olympic National Forest and Olympic National Park there were more than 90 trailside shelters in the Olympics. Many were developed through the guidance of Frederick William Cleator, who became one of the nascent US Forest Service’s first recreational specialists. Along with calling for trails, shelters, and fire lookouts, Cleator also advocated for a large portion of the Olympics to be left as wilderness, free from any developments.

The early shelters were meant to help administer the forest by providing rangers, trail workers and foresters a place to overnight while traversing the vast wild lands of the Olympics. But they were also welcomed by the few backpackers who plodded into the Olympic backcountry at the time. Through the years many of the shelters succumbed to fire, collapse and disrepair. And as recreational use increased and attitudes changed regarding land management, many hikers and land managers began to question the role of these structures in the wilderness. Under new directives many of the shelters were allowed to fall in disuse or were intentionally dismantled.

Many recreationists however continued to argue for the need of these shelters to provide emergency cover for backcountry users caught in severe weather. Many other recreationists including this author have argued to maintain the remaining shelters now numbering only around 20 as historically significant and preserve them as historic structures.

The Tunnel Creek Shelter is one of the last remaining in Olympic National Forest. Perhaps use it for a lunch break. Reflect on its long history and the role it has played providing refuge to many a wanderer on a cold and wet day. And help protect it from misuse. Beyond the shelter, the trail crosses via a log bridge the South Fork of Tunnel Creek and then gets down to business. They way now steadily and steeply climbs out of the valley ascending a thickly forested ridge. Eventually reach a small saddle in the ridge harboring two small bodies of water. The first is a small grassy pond known as Karnes Lake. Just beyond and a little higher up at 4.3 miles from the trailhead and at an elevation of 4300 feet is the more appealing Harrison Lake.

You don’t want to call it quits yet however. Conjure up a little more energy and continue hiking, ascending through open forest and over ledge coming to the 5050-foot ridge crest at 4.7 miles. Now take in an exceptional view of 7,743-foot (third highest peak in the Olympics) Mount Constance’s impressive sheer vertical east face.

You can scramble along the rocky ridge a little higher to better appreciate Constance’s towering presence, less than two miles away to the northwest.

For most hikers this is the turning around spot. But the trail continues from here making an insanely steep drop of more than 4300 feet in 3.6 miles to the Dosewallips River Road. It’s brushy in spots and easy to lose along the ridge. Otherwise it’s in decent shape down steep slopes and through old growth and past a small waterfall at Gamm Creek.

f you can arrange a car shuttle consider hiking out this route. There are some good views down to the Dosewallips River valley and out to Hood Canal during the initial descent if you want to just wander a little way down the trail. Otherwise start heading back to the cool forests of South Fork Tunnel Creek on the much more agreeable trail back to your start.

The details

Land Agency Contact: Olympic National Forest, Hood Canal Ranger District, Quilcene, (360) 765-2200,fs.usda.gov/olympic

Recommended Guidebook: Day Hiking Olympic Peninsula 2nd edition (Romano, Mountaineers Books)

Trailhead directions: From Shelton follow US 101 north for 50.5 miles. (From Quilcene, drive US 101 south for 1.5 miles). Turn left (west) onto Penny Creek Rd. After 1.5 miles bear left onto Big Quilcene River Rd (Forest Rd 27); which eventually becomes paved. At 3.0 miles bear left onto graveled FR 2740 and follow for 6.9 miles

Hamma Hamma's Living Legacy Trail

Take a leisurely hike back into time on this delightful trail along the Hamma Hamma River to the historic Hamma Hamma Cabin.

By Craig Romano, feature columnist

Craig Romano, is an author of more than twenty hiking guidebooks including the bestselling Day Hiking Olympic Peninsula 2nd Edition (Mountaineers Books), which includes detailed descriptions for 136 hikes throughout the Olympic Peninsula. Visit CraigRomano.com for more information.

Take a leisurely hike back into time on this delightful trail along the Hamma Hamma River to the historic Hamma Hamma Cabin. Constructed by the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC), the cabin was used as a guard station in Olympic National Forest. Today it stands as a testament to the craftsmanship and hard work of the CCC. Learn more about “Roosevelt’s Tree Army” and their legacy on this family friendly interpretive trail.

Photo: Craig Romano

In April of 1933 in the midst of the Great Depression, newly inaugurated president Franklin D Roosevelt established the CCC through an executive order. Roosevelt’s aim was more than just putting young men to work and allowing them to provide for their families.

"Roosevelt strongly believed in the spiritual and physical values of working in nature, and in the importance of conservation of our natural resources for the nation’s health and prosperity."

At its height in 1935, more than 500,000 young men were stationed in more than 2900 CCC camps in every state as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. At the program’s close in 1942, more than 3 million men (nearly 5% of the country’s male population) had served in the CCC. This trail sheds some light on what life was like for these men during their time in the Corp—and highlight some of their achievements and legacy.

Photo: Craig Romano

Among their many projects, CCC recruits were responsible for building vast amounts of infrastructure within parks and forests throughout the country—including both the Olympic National Park and Forest.

They also fought fires, reforested large tracts of land and worked on flood control projects. There were camps established right within Olympic National Park and Olympic National Forest, including one in the nearby Staircase Region. Nearby Twanoh State Park on Hood Canal also was the site of a large CCC camp.

Hit the Trail

Start your hike east on a wide and level path through a riparian forest of large mossy maples and speckled barked alders. The first quarter mile of this recently refurbished trail is ADA compliant. While this trail emphasizes the historic role the CCC played in this corner of Olympic National Forest, there is plenty of natural beauty to be enjoyed long the way as well. It is the only trail (albeit just for a short stretch) that runs along the Hamma Hamma River.

Photo: Craig Romano

The river’s name come from the Twana (whose ancestral lands included much of the Hood Canal region) word Hab’hab, which refers to a reed along the river’s banks. The name means big stink, or literally stinky, stinky in reference to the aroma the reeds emitted. The trail hugs a bank above the river allowing for some excellent views of the pretty waterway.

Photo: Craig Romano

Stop and look for dippers—robin sized birds that feed on aquatic insects and nest along the shorelines of rushing water. In spring look for Harlequin ducks returning from the Salish Sea. One of the prettiest sea ducks, they build hidden nests along rapid moving creeks and rivers.

The trail climbs a small bluff granting an excellent view of the pretty waterway, before leaving the river for forest. At 0.5 mile the trail turns north to cross Forest Road 25. Now walk along cascading Watson Creek climbing about 100 feet to a wooden bench on a perch overlooking the creek. It’s a great spot to sit and enjoy the sound of nature’s water music. By late spring nesting thrushes and other songbirds add a wide range of melodies.

The trail now turns west to soon reach the historic Hamma Hamma Guard Station. Built by the CCC from 1936 to 1937, it was used for administrative purposes for forest fire and trail crews. Today this eloquently rustic structure with its hexagonal bay window can be rented out for an overnight stay recreation.gov. Please respect the privacy of any guests staying at the cabin by not walking on the grounds. Otherwise wander around the structure. Note the landscaping too, especially the rhododendrons which will be in bloom come May.

Photo: Craig Romano

After admiring the historic structure continue west on the loop crossing a small creek and traversing a grove of mature second growth firs. The way then descends into a ravine before re-crossing FR 25. Continue hiking passing some big beautiful old trees before reaching the campground loop road near campsite no. 6. Now turn right and walk the loop road a short distance back to your start closing your loop hike at 1.8 miles. Reflect on some of the achievements of the Corp including the thousands of miles of trails they built, more than 3400 fire towers constructed, nearly 3 billion trees planted, and the development of amenities and infrastructure in more than 800 parks across the nation. Many of their works are still standing and in use in Olympic National Park and Olympic National Forest as well as at several nearby state parks. The Corp’s legacy continues to live on for the next generation of outdoorsmen and women.

Getting Here

First .25 mile ADA; Leave No Trace Principles

Land Agency Contact: Olympic National Forest, Hood Canal Ranger District, www.fs.usda.gov/olympic

Recommended Map: Green Trails Olympic Mountains East 168S

Trailhead directions: From Hoodsport travel north on US 101 north for 13.7 miles turning left at milepost 318 turn onto FR 25 (Hamma Hamma River Road). Then continue west for 6.0 miles turning left into the Hamma Hamma Campground. Proceed for 0.1 mile to trailhead located near site no. 12.

Trailhead facilities: campsites (fee), privy