Crossing the Bar - McMicken Island

There are no bridges or causeways to little McMicken Island in Case Inlet. No ferry service either. But you don’t need a kayak or boat to visit. You can easily hike to this island which lies about 0.2 mile off of the eastern shore of Harstine Island. It’s all in the timing.

Craig Romano | Story & images

There are no bridges or causeways to little McMicken Island in Case Inlet. No ferry service either. But you don’t need a kayak or boat to visit. You can easily hike to this island which lies about 0.2 mile off of the eastern shore of Harstine Island. It’s all in the timing.

When the tide is low, a tombolo (a sandbar connecting the island to the mainland—or in this case another island) is exposed allowing you dry foot access to the island. You then can hike the island’s small half mile trail, picnic in its small meadow, or explore big barnacle-encrusted rocks in its intertidal zone. Just mind the incoming tide lest you make a big splash on your island exodus.

Hit the Trail

The hike to little 11.5 acre McMicken Island begins from the 300-acre Harstine Island State Park. A former Washington DNR property, most of the old timber was logged off, but small groves of old-growth remains on the property.

You want to head to the park’s beach reachable by the two trails taking off south from the parking lot. Take the one on the eastern end of the lot (away from the kiosk) for the more direct route.

The trail heads towards Case Inlet soon reaching the edge of a 100 foot high forested bluff. Continue along the bluff taking in glimpses of the remote beach below. The way then descends into a cool and dark ravine graced with big cedars and firs and reaches a junction.

The trail to the right loops back to the other main trail leaving the parking lot. Consider taking it upon your return from McMicken Island.

Head left through a row of big cedars and via a series of steps descend deeper into the ravine. After crossing a little creek the way emerges on a deserted beach. Look directly across Case Inlet to Herron Island and the Key Peninsula. Then look south and spot McMicken Island set against a backdrop of big beautiful Mount Rainier. If the tide is high, you’ll have to wait to hike the beach as overhanging trees prohibit passage. But in a low tide, a big wide easy to walk beach awaits your footprints.

Walk for more than a mile undulating between cobbles, mud and sand. Watch for sand dollars scatted across the tide flats. Look too for eagles, herons and a myriad of seabirds. Harstine is a wet place and plenty of side creeks fan out on the beach. You should be able to keep your shoes dry, but a pair of waterproof boots is not a bad idea. The entire way to the tombolo is on public tidelands. But there is a parcel of private property located between two large state park properties abutting the shoreline. Respect posted private property.

The tombolo is pretty distinctive in low tides—fairly wide and several feet raised above inlet waters. In high tides it’s completely submerged, although breakers will help you locate its position. It’s really fun to hike it when a receding tide first reveals it. Tap your inner Moses and part the seas watching the land bridge emerge as you amble along it.

Reaching the island

Once across the .2 mile sandy strip, reach McMicken Island. All of the little island except for a small fenced parcel with a couple of cabins is state park property. The private holding belongs to the family that once owned the entire island. They sold the island to the state withholding this small lot. Please keep out of it. The rest of the island however you are free to explore.

At the island’s western end is a small picnic area in a grassy opening. Here find some rare Garry oaks growing on a low bluff above the surf. Near a composting toilet at the eastern edge of the field is a small nature trail. Hike it! It weaves a half mile through towering firs and madronas to blufftop views on the eastern end of the island.

Be sure to explore the rocky tide flats surrounding the island too, and check out the large erratics scattered about. There is a particularly large one on the south side of the island. Enjoy your island wanderings and explorations—more than likely sharing it with no more than just a couple of other happy hikers. And be sure to keep track of the time and incoming tide so you don’t get trapped on the island.

Places to Stay

Waterfront cabin located on Harstine Is with beach access and a panoramic view of the Puget Sound, Mt. Rainier and McMicken island. Check availability

Hike back to Harstine Island State Park and call it a day or consider walking some more. The park contains three miles of trails. They traverse thick fir forests and swampy cedar groves and are family and dog-friendly.

McMicken Island Notes:

Forest Setting with Beach Access

Cross the bridge to Harstine Is. and enjoy a beautiful and quiet retreat in the woods. Relax in the comfortably furnished cabin or enjoy exploring the 5 acre property with meandering trails through a lovely forest. Check availability

Distance: 4.0 miles round trip

Difficulty: easy, pay attention to tides! Hike is only possible in low tides. Consult tide tables and plan accordingly. Dogs permitted on leash.

Trailhead Pass Needed: Discover Pass

GPS Waypoints: Harstine Island State Park Trailhead: N47 15.737 W122 52.236 McMicken Island Trailhead: N47 14.865 W122 51.780

Features: Kid and dog friendly, beach hiking, undeveloped coastline, small island reached via a sandbar, good bird watching, sublime views of Mount Rainier over Case Inlet.

Trailhead directions: From Olympia, head north on US 101 to Olympic Highway (SR 3) Exit in Shelton. Then turn and follow SR 3 east for 11.0 miles. Turn right onto Pickering Road (Signed for Harstine Island) and drive 3.3 miles. Then bear left onto Harstine Bridge Road and come to a T-junction upon entering Harstine Island. Go left on North Island Drive and after 3.0 miles turn right at the island community hall onto East Harstine Island Road. Proceed for one mile and turn left onto Yates Road. Continue 0.9 mile and turn right into Harstine Island State Park. Reach trailhead parking in 0.2 mile.

A Guide to 25 Waterfalls from Canal to Coast and points between

Receiving hundreds of inches of rain annually, the Hoh, Quinault and Queets Rainforests are located on the coastal foothills of the Olympics, receiving 21+’ of snow and rain at its peaks! It’s no wonder there is a myriad of spectacular waterfalls lacing the area. Explore this sampling curated by celebrated guidebook author and avid hiker, Craig Romano. Some are small, secret, and unique, others are popular but magnificent. All are worth the journey!

When Craig Romano agreed to share with us a few of his favorite waterfalls in the Pacific Coastal region of Washington, we were frankly thrilled. If you’re looking for straight details on Northwest hikes and wilderness destinations — and fun facts - Craig is the guy to call.

Craig has written more than 20 hiking guidebooks including Day Hiking Olympic Peninsula 2nd Edition which includes details for popular and little known hikes across the Peninsula. An avid hiker, runner, paddler, and cyclist, Craig is currently working on Urban Trails Vancouver USA (2020); Backpacking Washington 2nd Edition (2021); and Day Hiking Central Cascades 2nd Edition (2022). He is also a featured columnist for the Fjord and Explore Hood Canal.

Enchanted Valley | Craig Romano photo

Why we are so keen about our falls?

As storms from the Pacific Ocean move across the peninsula, they crash into the Olympics and are forced to release moisture in the impact. Consequentially, the clouds release massive amounts of moisture (up to 170 inches annually) in the coastal side of the range – creating the “rain shadow effect.”

The massive rainfall has given life blood to the hanging mosses of the perpetually wet Northwest rainforests – Hoh and Quinault. On top the Olympic Mountains this moisture lands as snow frosting the peaks with as much as 35 feet each year.

Each spring the snow melts and creates icy run-off. Mix in a little more rainfall and the result is a spectacular waterfalls ring envelops the base of Olympic range.

Pacific coastal waterfalls are gorgeous year round but tend to be most spectacular in early spring or during the autumn rainy season.

Let’s go Chasing Waterfalls

1. Tumwater Falls

Olympia Metro | Located minutes from Olympia, Tumwater Falls is an iconic landmark near the state capital. These thundering multi-tiered showy falls along the Deschutes River are located within a 15-acre park created on land donated by the Olympia Brewing Company. Meander along manicured paths and saunter over foot bridges and under historic road bridges taking in a little history along with the sensational scenery.

At the base of the upper falls admire a replica of the famous bridge that once appeared on the labels of Olympia beer spanning the river above the lower falls. Walk trails along the gorge between the falls and admire deep pools, eddies and jumbled boulders. Take time to read the informative panels on Tumwater—Washington’s oldest permanent non-Native settlement on Puget Sound. Let’s Go!

2. Kennedy Creek Falls

Kamilche, South of Shelton | From its origin at Summit Lake in the Black Hills, Kennedy Creek flows just shy of 10 miles to Oyster Bay tumbling over a two-tiered waterfall along the way. Reaching these pretty falls involves a half day hike on a closed-to-vehicles logging road through patches of cuts and mature standing timber. Start walking across a recent cut. In about a mile reach a grove of mature timber and the Kennedy Creek Salmon Trail which opens in the fall for salmon viewing and field trips. Keep walking on the main road avoiding diverting roads. The route leaves state land for private timberland and rolls along. Take in decent views of the surrounding foothills. At 2.8 miles (just before crossing a creek) follow an obvious but unmarked trail to the right. This path can be muddy and slick during periods of heavy rainfall. The trail descends to a grove of big cedars, firs and yews—and the falls. Here Kennedy Creek tumbles over an ancient basalt flow. The upper falls are small but quite pretty. The lower falls are difficult to see as they tumble into a narrow chasm of columnar basalt. Let’s Go!

3. Vincent Creek Falls

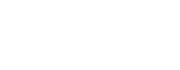

South Hood Canal, Skokomish Valley | While Vincent Creek Falls are quite stunning crashing 250 feet into the South Fork Skokomish River in a deep narrow canyon; the High Steel Bridge which allows for their viewing is even more spectacular. The 685-foot long bridge spans 375 feet above the canyon. Walk across the bridge but use caution along its north side where the guardrail is only 3 feet tall. The arched truss steel bridge was built in 1929 originally for a logging railroad. In 1950 it was converted for road use. It is the 14th highest bridge in the country. Your heart is sure to pound as you walk upon its airy span. Eventually Vincent Creek Falls comes into view. Through a series of falls, Vincent Creek drops 250 feet down a canyon wall into the roaring South Fork Skokomish River. Walk all the way across the bridge if you plan on capturing the falls in their entirety in a photo. Let’s Go!

Big Creek | Craig Romano Photo

4. Big Creek Cascades

Lake Cushman Area, Hood Canal | Amble on a circuitous route in the Big Creek drainage within the shadows of Mount Ellinor; and delight in a series of small tumbling cascades. This wonderful loop utilizes old logging roads, new trails and a series of beautifully built bridges. It was constructed by an all-volunteer crew that continues to improve and maintain this excellent family and dog-friendly loop. Starting from the Big Creek Campground, follow the Upper Big Creek Loop Trail to Big Creek and the first of several sturdy bridges along the way. After a short climb you’ll reach the Creek Confluence Trail which drops to the confluence of the tumbling Big and North Branch Creeks. The main loop continues to cross North Branch Creek on a good bridge. Just beyond it crosses Big Creek on a new bridge above a gorgeous cascade. The loop then descends skirting big boulders and passing good views of roaring Big Creek. It crosses a couple more cascading creeks before traversing attractive forest and returning to the campground. Let’s Go!

5. Staircase Rapids

Lake Cushman Area, Hood Canal — Currently Closed until mid-September

This loop involves a section of an historic route across the Olympic Mountains to a suspension bridge spanning the North Fork Skokomish River near a series of thundering rapids. Cross the North Fork Skokomish on a solid bridge and follow a trail that was once part of the original O’Neil Mule Trail. In 1890 Lieutenant Joseph O’Neil accompanied by a group of scientists led an Army expedition across the Olympic Peninsula. Among his party’s many findings was a realization that this wild area deserved to be protected as a national park. March up alongside the roiling river, passing big boulders and a series of roaring rapids. The rapids’ name come from a cedar staircase O’Neil built over a rocky bluff to get past them. Follow the bellowing river from one mesmerizing spot to another before reaching a sturdy suspension bridge spanning the wild waterway. Cross the river and complete this delightful loop by now heading downriver following the North Fork Skokomish River Trail back to the Ranger Station. Let’s Go!

Hamma Hamma | George Stenberg photo

6. Hamma Hamma Falls

Hamma Hamma River Valley, Hood Canal | Talk about a bridge over troubled waters. From the Mildred Lakes Trailhead walk across the high concrete bridge at the road’s end. You no doubt heard the roar of the falls when you drove across it. Now peer over the bridge and witness the cataracts responsible for the racket.

Directly below, the Hamma Hamma River careens through a tight rocky chasm. These impressive falls are two-tiered crashing more than 80 vertical feet. The road spans directly above the upper and smaller of the falls. The overhead view is pretty decent, but the lower and larger falls are more difficult to fully see. A very rudimentary path leads along cliff edges for better viewing, but it’s slick, exposed and treacherous.It’s best to experience the falls from the safety of the bridge. During periods of high water flow you’ll get the added bonus of feeling the falls too thanks to a rising mist. On the drive back look for a couple of pull-offs providing views of secondary falls along the Hamma Hamma, Let’s Go!

7. Murhut Falls

Duckabush River Valley, Hood Canal | Hidden in a lush narrow ravine and once accessed by a treacherous path, Murhut Falls were long unknown to many in the outside world. But now a well-built trail allows hikers of all ages and abilities to admire this beautiful 130-foot two-tiered waterfall. The trail starts by following an old well-graded logging road. It was past logging in this area that led to the discovery of these falls. The old road ends after a short climb of about 250 feet to a low ridge. The trail then continues on a good single track slightly descending into a damp, dark, cedar-lined ravine. As you work your way toward the falls, its roar will signal you’re getting closer. Reach the trail’s end and behold the impressive falls crashing before you. The upper falls drops more than 100 feet while the lower one crashes about 30 feet. Blossoming Pacific rhododendrons lining the trail in May and June make the hike even more delightful. Let’s Go!

Rocky Brook Falls

8. Rocky Brook Falls

Dosewallips River Valley, Hood Canal | One of the tallest waterfalls on the Peninsula, Rocky Brook Falls is also among the prettiest. Follow the trail past a small hydroelectric generating building and come to the base of the stunning towering falls fanning over ledges into a large splash pool surrounded by boulders. This classic horsetail waterfall crashes more than 200 feet from a small hanging valley above. While a penstock diverts water from the brook for electricity production, the flow over the falls is almost always pretty strong. Like all waterfalls, these too are especially impressive during periods of heavy rainfall. On warm summer days the falls become a popular destination for folks seeking some heat relief. And while many waterways east of the Mississippi River are called brooks, creek is the preferred name in the west. There are only a few waterways on the Peninsula called brooks, and they were more than likely named by someone who hailed from back east. Let’s Go!

9. Dosewallips Falls

Dosewallips River Valley, Hood Canal | This spectacular waterfall used to be easily reached by vehicle. But the upper Dosewallips Road has been closed to vehicles since 2002 after winter storms created a huge washout that has yet to be repaired. Now to reach this waterfall you must hike or mountain bike the closed road. Walk past the road barrier and immediately come to the washout and a bypass trail. Steeply climb on the riverbank above the slide. Then descend back to the road and walk along the churning river. The road then pulls away from the river, passes a campground and climbs. The river now far below in a canyon is out of sight, but not out of sound. Pass beneath ledges and cross cascading Bull Elk Creek on a bridge. At 3.9 miles in a recent burn zone enter Olympic National Park. Cross tumbling Constance Creek on a bridge and continue climbing passing a big overhanging boulder. Then descend and skirt beneath a big ledge coming to the base of dramatic 100-foot plus Dosewallips Falls. Admire the raging cascade’s hydrological force—it’s mesmerizing. Let’s Go!

10. Fallsview Falls

Big Quilcene River Valley | As far as cascades go, Fallsview Falls lacks the “Wow factor.” However the canyon these falls tumble into is pretty impressive. And if you plan your visit for late spring, blossoming rhododendrons line the trail and frame the view with brilliant pinks and purples. The trail to the falls is short, easy and ADA accessible. Follow the 0.2 mile loop to a fenced promontory above a tight canyon embracing the Big Quilcene River. Gaze straight down to the roiling river. Then cast your glance directly across the canyon to an unnamed creek cascading 100 feet into it. By late summer it just trickles—but during the rainy season the falls put on a little show. If you want to stretch your legs some more afterward, you can follow a trail into the little canyon and hike along the frothing river. Let’s Go!

And 15 more…

For a day trip, weekend, or a month-long adventure – the Olympic Peninsula is a fantastic place to get away and enjoy nature – and waterfalls! It’s not just 1000’s of waterfalls, there are countless lakes, rivers, streams and trails to suit every ability level. Embraced by the Pacific Ocean on the west, the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the north, and the Hood Canal on the east, it is famed for being home to Olympic National Park, more than 600 miles of hiking trails and 73 miles of pristine ocean wilderness beaches.

The Olympic Peninsula hosts activities for families and outdoor enthusiasts alike, attracting visitors from near and far. Start planning your next adventure!

Click here for a complete list of all 25 waterfalls on the Olympic Peninsula curated by Craig!

Bird’s Eye View from Mount Townsend

Mount Townsend is a prominent landmark — and one of the region’s most hiked peaks. Its broad open summit affords sweeping views of some of the highest and craggiest peaks in the Olympics and a myriad of islands, straits, bays and peninsulas below.

Story & Photos: Craig Romano

Mount Townsend | photo credit Craig Romano

Rising more than 6200' at the northeast edge of the Olympic Mountains, Mount Townsend is a prominent landmark — and one of the region’s most hiked peaks. Its broad open summit affords sweeping views of some of the highest and craggiest peaks in the Olympics and a myriad of islands, straits, bays and peninsulas below. Stand atop this mountain on a clear day and watch ferries and vessels ply the shimmering waters below. Marvel at the Seattle skyline against a backdrop of snowy Cascade Mountains dominated by big, beautiful Mount Rainier. Ascend Townsend in the summer and be greeted by a brilliant array of wildflowers swaying in the alpine breezes.

Hit the Trail

There are four ways you can hike to get to the summit of Mount Townsend and all of them offer great views and a good workout. The most popular route to the mountain is the Mount Townsend Trail from its upper trailhead. An out and back via this route clocks in at 8.2 miles with just shy of 3000 feet of elevation gain. But if you don’t mind a slightly longer hike with a little more elevation gain, consider starting from the Lower Trailhead.

Throughout much of this hiking season you just may have to start from the Lower Trailhead as the Forest Service works on the upper trailhead access road rendering it off limits while under construction.

The Lower Trailhead start will add two more miles to your total roundtrip and another 500 feet of elevation gain. But it’s worth it. The way traverses a beautiful grove of primeval forest and passes by tiny Sink Lake where Townsend Creek performs a disappearing act. After one mile of pleasant walking you’ll emerge at the upper trailhead. As you approach the trailhead what may be an unsightly situation. The lack of an outhouse at such a popular trailhead as led many to violate leave no trace principles with some bad bathroom etiquette. Perhaps a note to the Forest Service in support of a trailhead privy can help rectify this situation.

From the Upper Trailhead, follow a well-beaten path and steadily ascend. The trail weaves through a stately grove of Douglas-fir and western hemlock adorned with Pacific rhododendrons. Time your hike for late May through June and enjoy brilliant blossoms. After a half mile enter the Buckhorn Wilderness protecting more than 44,000 acres of spectacular terrain in the Olympic Mountain’s northeastern rain shadow. Continue climbing transitioning into more open forest and start catching views that will only improve in magnitude as you carry on.

Cross several cascading creeks as you follow copious switchbacks upward.

At just past 2.5 miles reach a small pine and fir grove nestled on a small knoll just above tiny Windy Lake. And do hope the lake lives up to its name or its resident bugs may force you to move quickly through the area. In another half mile reach the scenic trail to the Silver Lakes. Bear right and soon leave the trees behind as you attain Townsend’s summit plateau.

Now traverse the subalpine tundra that upon a quick glance may appear barren. But it’s full of life and in summer beaming with color thanks to a myriad of wildflowers; cinquefoil, phlox, paintbrush, and harebells among them.

Look too in the rocky areas for Piper’s bellflower, a campanula that is endemic to the Olympic Mountains. Owing to its drier aspects, junipers hug the ground throughout Townsend’s summit.

At 4.0 miles from the upper trailhead reach a junction. The main trail continues left descending to the Little Quilcene Trail offering two more approaches to the summit—one from the Northwest and one from the Northeast. Head right for 0.1 mile to the mountain’s highest point, its 6280-feet south summit. Consider continuing on the trail a short distance to Townsend’s northern 6212-foot summit too. It was on this point from 1933 until 1962 that a fire lookout once sat.

The views are great from anywhere along the open peak. Gaze out to the Salish Sea with its sprawling labyrinth of islands, bays, and channels. Watch ferries ply azure waters. Marvel at the Seattle skyline sparkling in the afternoon sunlight. And admire a fortress of Cascade peaks, punctuated by the snowy volcanoes. Look north to Dungeness Spit, Discovery Bay, the San Juan Islands, and Vancouver Island. And to the west, it’s nothing but pure Olympic wilderness—jagged peaks and deep green valleys.

And if you’re wondering if Townsend (as well as the nearby city and port) takes its name after the 19th century naturalist who named Townsend’s chipmunk, Townsend’s ground squirrel, Townsend’s solitaire and many other species—it is not!

Captain George Vancouver in 1792 bestowed the name Townsend—originally Townshend for the Marquess of Townshend. The father of Thomas Mamby, one of Vancouver’s crew members was an aide-de-camp to the Marquess at the time. The S’Klallam Tribe which had a community on the bay at the time originally called it Kah Tai which translates to pass through. You’ll probably want to pass through Mount Townsend on a return trip by perhaps ascending it via one of the other routes.

Mount Townsend Details

Distance: 8.2 miles roundtrip

Elevation Gain: 2980 feet

High Point: 6280 feet

Difficulty: moderately difficult

Snow free: June to November

Trailhead Pass Needed: None

Notes: trail also open to horses, wilderness rules apply

GPS waypoints: Trailhead: N 47 51.385, W 123 02.153

Land Agency Contact: Olympic National Forest, Hood Canal Ranger District, Quilcene; http://www.fs.usda.gov/olympic

Recommended Guidebook: Day Hiking Olympic Peninsula 2ed (Romano, Mountaineers Books)

Trailhead facilities: none

Trailhead directions: From Shelton, drive US 101 north for 50.5 miles. Upon crossing the Big Quilcene River just shy of the community of Quilcene turn left onto Penny Creek Road. The drive 1.5 miles and bear left onto Big Quilcene River Road (Forest Road 27). Follow this generally good road for 12.5 miles for the lower trailhead turnoff; or 13.7 miles for the upper turnoff. Then reach the lower trailhead in 0.8 mile or the upper trailhead in 0.7 mile.

Feast your eyes on a face with personality to spare!

Get any group of divers together in the Pacific Northwest and ask them what makes for a great dive. Everyone will agree that a wolf eel was somehow involved. There is something unique about the supremely ugly faces of an adult wolf eel staring at you from its den.

Story & Pictures, Thom Robbins

Get any group of divers together in the Pacific Northwest and ask them what makes for a great dive. Everyone will agree that a wolf eel was somehow involved. There is something unique about the supremely ugly faces of an adult wolf eel staring at you from its den.

Hood Canal Wolf Eel | Photo credit: Thom Robbins

This can turn an ordinary dive into a great one. The conditions don’t matter – cold, terrible visibility or strong currents are forgotten once a wolfie (as we call them locally) appears publicly. It’s not surprising why divers worldwide travel to places like the Hood Canal to catch a glimpse of these fantastic creatures.

Meet wolfie

Hood Canal Wolf Eel | Photo credit: Thom Robbins

Throughout history, the peoples of the northern Pacific have held wolf eels in deep respect. Many of the native tribes in the area viewed the wolf eel as a creature of strength and resilience, symbolizing protection due to its robust and intimidating appearance. This belief often extended to the spiritual realm, where the wolf eel was thought to embody protective spirits. In Washington, the wolf eel is now a protected species in the Puget Sound and Hood Canal.

This is not because they are endangered but because their value as a living resource to divers and photographers far exceeds whatever commercial value the species could provide as a food source. Some dive sites, like Sund Rock in the Hood Canal, are well-known locations where wolf eels interact with divers and provide unique photo opportunities.

Wolfies are not related to eels. Instead, they are part of a family known as the wolf fishes.

Hood Canal Wolf Eel | Photo credit: Thom Robbins

They belong to an even larger group of fish known as Perciform, generally considered perch-like fish. But their long-bodied, eel-like appearance is unique in this group of fishes. The wolf eel can be found as far south as San Diego in southern California, then northward up the Pacific coast to the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. The popular term “wolf eel” comes from the large frontal canine-like teeth used to seize their favorite meals, mainly hard-shelled crustaceans and invertebrates. The typical menu includes crabs like Dungeness, Red Rock, and Green Urchins.

Most wolf eels can grow to about six feet long and weigh almost thirty pounds, although they can grow to eight feet. These massive fish are speculated to live up to 10 years in the wild, though no research is available on their longevity. Scientists have found that they can begin reproducing between four to seven years, suggesting they may be long-living fish. One fact that I find fascinating is that they lack a swim bladder, a feature commonly found in most fish species. The swim bladder is an internal gas-filled organ that helps fish regulate their buoyancy and control their vertical position in the water column. However, the wolf eel has evolved without this organ, relying on its muscular body and strong pectoral fins to maneuver and maintain its position in the water. The lack of a swim bladder allows wolf eels to lounge around on the bottom or lay in their home lairs. Like snakes, they swim by making S shapes with their bodies and use their pectoral fins to steer. This unique adaptation allows the wolf eel to thrive in rocky coastal habitats, where it can navigate through crevices and caves with exceptional agility. By forgoing the swim bladder, the wolf eel has developed a specialized set of skills, making it an expert hunter and a master of its underwater domain.

Additionally, wolf eels have a slimy coating on their bodies, which serves several important purposes for their survival and protection in their marine environment. First, it acts as a natural defense against infections. The slime contains antibacterial and antimicrobial properties that help prevent the growth of harmful bacteria and parasites on their skin, reducing risk of infection.

The slimy coating makes it difficult for predators to grip or hold onto a wolf eel.

When threatened or attacked, a wolf eel can release more slime from its skin, making it slippery and challenging for predators to maintain a firm grip. This slippery defense mechanism allows the wolf eel to escape from potential threats. The slimy layer reduces friction when the wolf eel moves through the water, allowing them to easily pass through tight spaces and narrow cracks without getting stuck.

Lifecycle of a Wolf Eel

Approximately 24 hours before mating, the female wolf eel’s abdomen becomes noticeably distended. When this happens, the male will butt his head against the back of her abdominal region. This action appears to stimulate physiological activity. A series of waves move through the female's body from her head to her tail, particularly pronounced in her abdominal area. The male will then wrap himself around the female so that their heads will be side by side and their genital regions adjacent. In this position, the female releases the eggs, usually between 5,000 and 10,000, and the male fertilizes them as they appear. After fertilization, the female will coil about the eggs, molding them into a ball-like cluster. The eggs are adhesive to each other but not to the rocky walls of the den. Both parents will then coil themselves about the egg mass, sometimes together and at other times individually, tending the eggs and ensuring they are rotated so that a good flow of water passes through them.

After about 16 weeks, the eggs hatch, and the larvae float towards the upper part of the ocean or the sea, where they spend nearly two years of their lives. The tiny fish are born brownish pink, about 1 1/2 inches long. They turn dark gray within a day and start snacking on small shrimp after a few days. The larvae that emerge are left on their own to swim with the plankton in the ocean. From birth, they are voracious predators and will strike at their planktonic prey, much like a coiled snake will strike at a mouse. Constantly searching for prey, the larval wolf eels will lead a pelagic existence. Eventually, the maturing youngsters settle on the ground and enter a den. Denning will typically occur in the Puget Sound area from February through April.

Juveniles wolf eels exhibit a more vibrant and striking appearance. | Photo credit: Thom Robbins

The change from a pelagic to a bottom-dwelling existence spawns physical changes in the juvenile wolf eel. Juveniles exhibit a more vibrant and striking appearance. A vivid orange or reddish-orange color with darker markings often characterizes their appearance. This vibrant coloration helps juveniles blend in with their surroundings, such as rocky reefs or kelp forests. As they mature into adults, their coloration becomes more subdued brown or reddish-brown. The skin often has spots of a darker color, which may be outlined in a lighter color. The males will also develop a puffy face, enlarged jaws, huge bulbous lips, and a powerful sagittal crest at the top of their heads to support the increased muscle mass required for the jaws.

Friends & enemies

There is no fairness in the realm of a Salish Sea rocky reef. A fierce battle for ownership unfolds around the most desirable den sites. The key contenders are the Giant Pacific Octopus (GPO), and the formidable wolf eel.

Both species vie for control over these coveted shelters, which serve as their sanctuary in a harsh underwater world. This struggle is fueled by their shared habitat, prey, and an unyielding desire for the same type of den sites.

With its unmatched dexterity and cunning, the octopus poses a formidable challenge to the wolf eel. I have watched the battle when a GPO ruthlessly evicts a wolf eel, sometimes even targeting mated pairs, and claims the den as its own. Despite the wolf eel's valiant efforts, there is little it can do once an octopus of even modest size has set its sights on a particular den.

Ask any diver, and they can attest to the futility of trying to dislodge an entrenched octopus from its chosen abode.

Submerging into the chilly embrace of the Salish Sea transforms the ordinary into the sublime. A serene quietness wraps around you as you descend below the waves, echoing the solitude of an explorer charting new frontiers. Gripping your camera firmly, you traverse this alien landscape, feeling every inch an astronaut on an oceanic planet.

Hood Canal Wolf Eel | Photo credit: Thom Robbins

Before long, you approach a wall, its vastness urging you to uncover. You glide along its face, examining each nook, cranny, and boulder with a mix of awe and curiosity. The vividly colored marine life enchants you, each organism a stroke of brilliance from nature’s palette. In this marine maze, your adventure takes a thrilling turn.

From the periphery, a wolf eel appears, locking eyes with you. There’s a mutual recognition, a shared wonder between you and the creature, silently communicating in this mesmerizing undersea world. The thrill of the encounter sharpens your focus, and with camera in hand, you ready yourself to document this surreal moment. You aim and capture the scene, forever preserving your encounter with the wolf eel.

Hood Canal Diving:

Sund Rock Marine Preserve

26472 US-101, Hoodsport

sundrock.com

YSS Dive Charters

24080 N US-101, Hoodsport

yssdive.com/charters

About the Author: Thom Robbins

"Fascinated with the underwater world in the Pacific Northwest,I have been a diver for over thirty years and have never been happier than underwater with a camera. I spend as much time underwater as possible, shooting pictures or teaching diving and photography. You can see and purchase my photo collections at robbinsunderwater.com. If you want to learn about diving or photography, reach me at thomrobbins@gmail.com.

When not diving, I spend time with my wonderful, patient wife, Barb. We have just relocated to Shelton to enjoy a more relaxed life. Without Barb, I wouldn’t have continued my passion for diving. She is my best and often harshest critic, pushing me to explore better photos. I also have a 21-year-old son who makes me want to be a better person daily. Last but certainly not least are my two English Bulldogs, essential to my family's life."

Squatch Watch

The deep, extensive forests of the Olympic Peninsula hide secrets. For some its the discovery of a new plant that can cure an illness; others seek the solitude of moss laden ancient trees; and, for a select few, the search continues for a hidden creature that makes himself popular on bumper stickers and dangly air fresheners throughout the Northwest – here’s some details behind this northwest favorite character.

The deep, extensive forests of the Olympic Peninsula hide secrets. As the ancient coelacanth, a fish found in fisherman’s nets off of the coast of South Africa in 1938, or the chance discovery of the brilliantly bioluminescent megamouth shark (Megachasma pelagios) hooked upon a US Navy’s ships anchor in 1976, document --- the natural world still holds mysteries.

Before actual specimens of these species were found stories abounded about their existence, but proof was necessary to take these animals from the realm of cryptid to the empirical world. Cryptozoology is a term coined in the 1950s by Bernard Heuvelman, a French-Belgian biologist, used to describe the discipline responsible for documenting cryptids or “animals of unexplained form or size, or unexpected occurrence in time or space.”

The search for these cryptids or “hidden animals” has included research in to the Loch Ness Monster (Nessie) of Scotland, the Abominable Snowman or Yeti of the Himalayas, and the Lake Champlain monster (or Champ). More locally there are reports of sea serpents (often known as the Cadborosaurus) in the waters of the Salish Sea and Puget Sound and the Ogopogo lake monster of British Columbia’s Lake Okanagan. Another famous cryptid found across North America is the Bigfoot, or more locally, the Sasquatch.

"About one-third of all claims of Bigfoot sightings are located in the Pacific Northwest."

Washington State has the highest instance of direct sightings in the United States of creatures meeting the description of Sasquatch or "Bigfoot." Recorded by the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization (BFRO), Pierce County takes the lead with total number of listings, with Snohomish and Skamania following close behind. After a series of sightings and findings of foot prints and other evidence, Skamania famously passed a law in 1969 that forbade the “willfull and wanton slaying” of a Sasquatch. Such action would be considered a felony and punishable by a hefty fine of $10,000 and jail time. This punishment has since been reduced to $500 and only six months in jail, but the endurance of this legislation demonstrates that the Sasquatch is still considered real enough to protect.

"The endurance of this legislation demonstrates that the Sasquatch is still considered real enough to protect."

Stop by Bear in a Box in Allyn WA for some amazing squatch art.

Sasquatch has been described as a large, hairy, up-right walking, hominid-like creature, often accompanied by a strong stench. The Sasquatch is often identified by strange “eerie” calls such as whoops and screams. Additionally, it is famous for its large footprints. Usually, these encounters are reported as non-aggressive but they often induce incredible fear and a feeling of unease in the witness and there are reports of Sasquatches breaking large branches and throwing rocks.

Indigenous people throughout the Pacific Northwest describe in their oral history and legends various versions of a Sasquatch-like-creature that is often characterized as a malevolent trickster responsible for stealing children and women.

The Kwakwaakaa’wakw of Northern Vancouver Island, British Columbia, tell stories of Dsonoqua—or the Wild Woman of the Woods—who makes the noise of the wind “ooh-ing” through the trees and lures away children. These stories may or may not be cultural traditions documenting the Sasquatch.

Many a campfire is made spookier by tales of the supernatural Sasquatch. Stemming from this, there is a new kind of tourism on the rise—cryptotourism. Professionally led expeditions are orchestrated by organizations such as the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization (BFRO) and the Olympic Project to systematically search for evidence of the Sasquatch in areas of high reports. Usually, participants on these expeditions are taught in the field how to take accurate casts of footprints, make sound recordings, conduct surveys, as well as how to collect uncontaminated samples of hair and feces.

On the Lookout for Sasquatch

According to David George Gordon, author of The Sasquatch Seeker’s Field Manual (2015), mainstream researchers do not have access to the grants or time needed to properly assess the Sasquatch question, so like the Christmas Bird Count miraculously organized by Cornell every winter, volunteer, amateur scientists, or ‘citizen scientists,’ are the only hope to document evidence of the Sasquatch.

Training citizen scientists through organized expeditions is one way to further research and cover more ground. Additionally, these organizations file reports of Sasquatch sightings, lending us a powerful tool to create your own self-guided, cryptotour of the Olympic Peninsula.

Make sure you pack a good camera in the hopes you spot some unusual wildlife. As well, bring a friend or two as the more witnesses the more credible your evidence will be. Below are two top areas to look for Sasquatch activity in around Hood Canal from the BFRO’s list of Bigfoot reports.

Local Sightings & Reports

Jarell Cove State Park and Harstine Island area

• Report of an actual sighting in 2005

• Recent increase reports of hearing the calls of Sasquatches

Big Creek Campground & Lake Cushman area

• Report from hikers on Big Creek Trail of hearing the calls, smelling the stench and seeing oddly broken branches in 2010

• Multiple reports of hearing calls of Sasquatches in the Lake Cushman area

• Two reports of actual sightings in the Lake Cushman area from 2006.

Celebrate Oysters on Hood Canal

It's ok to be "shellfish" when your on Hood Canal. How about waking up to spectacular canal views for days filled with walks and beach treasure hunts? With spring weather on its way and the water warming up -t’s a great time to hit the Hood – and we’ve prepared a jam-packed customizable seafood itinerary for you.

It’s a great time to head to Hood Canal and South Puget Sound and start enjoying fresh oysters on the beach.

We’ve got a few ideas to get you “shell-e-brating” as well as a recipe from Xinh Dwelley to make your mouth water for some oyster love!

Xinh’s Grilled Oysters on the Half Shell

Recipe courtesy of Xinh Dwelley, celebrated seafood chef, Shelton, WA

(even the non-oyster eaters love these)

Prepare sauce in advance:

1/2 chopped red pepper, chopped

1/4 cup softened butter

1/2 cup chopped onion

Juice of 1 lemon

Salt and pepper to taste

2 tsp garlic, chopped

2 tsp soy sauce

1 tbsp hoisin sauce

1 tsp sugar

1/2 cup chopped chives

1/2 cup grated parmesan cheese

Combine ingredients in a blender and blend. Store in fridge until ready to prepare grilled oysters.

Place oysters on hot grill( 24-36 in shell). When shells begin to “pop” remove top with a heat-safe glove and top each with one teaspoon of mixture. Garnish with sprinkling of grated parmesan cheese ( about ½ cup total). Cook oysters are light brown and cheese has melted, 5-10 minutes. Serve hot.

Oyster Pairing: Serve with Sunlit Canyon Cellars’s Pinot Gris ($22) available at Cameo Boutique in Union. Sunlit Canyon small batch wines are grown and bottled in Belfair WA overlooking Hood Canal.

Save some Clams & Visit Mid-week

Perhaps a few oysters will suffer, but who doesn't like to save a little money?

For great deals on lodging, not to mention more selection, consider heading to the Canal mid-week to enjoy activities you will not find anywhere else. Pack up boots, buckets and license and head to parks and DNR beaches that are regularly stocked with shellfish for the taking. Yes, taking! Check the tides before you head out. Another advantage to mid-week shellfish-gathering is you'll have the beach to yourself! Visit the DFO Shellfish Safety Map as seasons are beach specific. Always Check BEFORE you dig. We've prepared a handy list of area harvesting beaches here.

Alderbrook Resort & Spa is a great place to start a Oyster tradition - especially since April is their official Oyster Month! Not only can they harvest oysters right on their beach, serve some great Hood Canal oyster dishes on their daily menu in the restaurant.

Alderbrook Resort, view from the dock (left); view from 2 Margaritas' patio seating (top middle); Robin Hood Village Resort onsite restaurant (top right); Cedar Hill Cottage, Union (bottom middle); Hood Canal Marina & location of the Canal Cookout in Union (bottom right)

Want the house all to yourself? Consider snagging one of the great rentals that pepper coastal communities and woodland oases in the area. One of our favorites is the Cedar Hill Cottage in Union. This spacious shake home (two bedrooms) is perched on the hill above Union, and although it is technically not waterfront and nestled in the woods, there are glimpses of the Canal and the snow laden Olympics. Location is everything here. A short drive to Alderbrook Resort and just a quick walk to the heart of Union with coffee and bakery items at the Union Country Store, boutique shops, and waterfront dining at 2 Margaritas.

Farm visits

Heading into Shelton, stop in off Hwy 101 past Little Creek Casino & Resort at Taylor Shellfish's Retail Facility to take a look at their headquarter facility and visit their retail store. Taylor Shellfish is a huge supporter of the annual West Coast Oyster Shucking Championship (OysterFest) by supplying over 1200 oysters to the competition!

Hama Hama Oyster Company in Lilliwaup serves farm fresh oysters and clams in their streetside Saloon off Hwy 101. Check out the Oyster Saloon, an outdoor farm dining experience, Thursday through Sunday. The retail store is open daily.

One of the area’s most popular oyster growers is located just 30 minutes away in Lilliwaup, WA. Hama Hama Oyster Company's Store and Oyster Saloon (an outdoor restaurant) are located a shell’s-throw from the tideflats. Visit during the week to see the shucking crew in action, and ask for one of their self-guided tour maps to better explore the farm. Stop by the Saloon (Thursday though Sunday) for some great shellfish but don't miss the divine hand-packed Dungeness crab cakes. And we mean PACKED with crab! The crab cakes are also available the farm store where you can buy them to cook at home.

How ever you choose to Shell-e-brate oysters we know that you will have a blast exploring Hood Canal. Be sure to share your adventures with the bivalves with us at #wildsidewa!

See you on the beach!

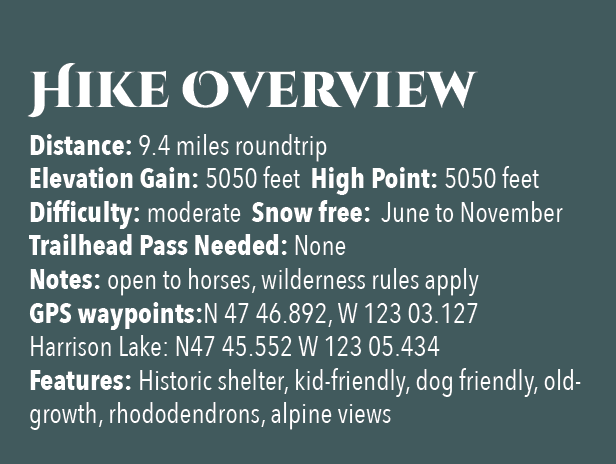

Tunnel Creek Trail Hike

Olympic National Forest’s Tunnel Creek Trail lies just a few miles south of the popular Big Quilcene Trail. But unlike the Big Quil which leads to Marmot Pass, a high windswept wildflower-rich gap providing sweeping views—the Tunnel Creek trail travels mainly beneath a thick canopy of primeval forest.

Craig Romano | author

Olympic National Forest’s Tunnel Creek Trail lies just a few miles south of the popular Big Quilcene Trail. But unlike the Big Quil which leads to Marmot Pass, a high windswept wildflower-rich gap providing sweeping views—the Tunnel Creek trail travels mainly beneath a thick canopy of primeval forest. Lacking the wow factor of Marmot Pass, Tunnel Creek gets passed over by many a hiker. However, those who take to this trail less taken soon discover; Tunnel Creek offers plenty of delightful spots and some pretty decent views as well. And all without the crowds of Marmot Pass.

Hit the Trail

The Tunnel Creek Trail immediately enters the 44,258-acre Buckhorn Wilderness, the largest roadless area in Olympic National Forest. Much of the wilderness lies within the Olympic rain shadow encompassing some of the driest mountainous terrain in the Olympics. But here at the wilderness’s southern reaches, precipitation increases. And it’s noticeable immediately upon starting up the trail. The surroundings are verdant—draped in mosses and lichens. The trees are grand. And the valley is alive with the sound of cascading water.

Work your way up a tight valley following alongside tumbling South Fork Tunnel Creek through a tunnel of towering old-growth western hemlocks and Douglas-fir. The hike is magical, almost ethereal on a misty morning. And it’s welcoming on a sweltering summer day, as the ancient trees do an excellent job of regulating the temperature, providing some much appreciated air-conditioning.

After 3.3 miles and gaining a modest 1500 feet of elevation, reach the still intact Tunnel Creek Shelter. A remnant from when this trail was much longer (before logging and roads obliterated much of it). In the early days of Olympic National Forest and Olympic National Park there were more than 90 trailside shelters in the Olympics. Many were developed through the guidance of Frederick William Cleator, who became one of the nascent US Forest Service’s first recreational specialists. Along with calling for trails, shelters, and fire lookouts, Cleator also advocated for a large portion of the Olympics to be left as wilderness, free from any developments.

The early shelters were meant to help administer the forest by providing rangers, trail workers and foresters a place to overnight while traversing the vast wild lands of the Olympics. But they were also welcomed by the few backpackers who plodded into the Olympic backcountry at the time. Through the years many of the shelters succumbed to fire, collapse and disrepair. And as recreational use increased and attitudes changed regarding land management, many hikers and land managers began to question the role of these structures in the wilderness. Under new directives many of the shelters were allowed to fall in disuse or were intentionally dismantled.

Many recreationists however continued to argue for the need of these shelters to provide emergency cover for backcountry users caught in severe weather. Many other recreationists including this author have argued to maintain the remaining shelters now numbering only around 20 as historically significant and preserve them as historic structures.

The Tunnel Creek Shelter is one of the last remaining in Olympic National Forest. Perhaps use it for a lunch break. Reflect on its long history and the role it has played providing refuge to many a wanderer on a cold and wet day. And help protect it from misuse. Beyond the shelter, the trail crosses via a log bridge the South Fork of Tunnel Creek and then gets down to business. They way now steadily and steeply climbs out of the valley ascending a thickly forested ridge. Eventually reach a small saddle in the ridge harboring two small bodies of water. The first is a small grassy pond known as Karnes Lake. Just beyond and a little higher up at 4.3 miles from the trailhead and at an elevation of 4300 feet is the more appealing Harrison Lake.

You don’t want to call it quits yet however. Conjure up a little more energy and continue hiking, ascending through open forest and over ledge coming to the 5050-foot ridge crest at 4.7 miles. Now take in an exceptional view of 7,743-foot (third highest peak in the Olympics) Mount Constance’s impressive sheer vertical east face.

You can scramble along the rocky ridge a little higher to better appreciate Constance’s towering presence, less than two miles away to the northwest.

For most hikers this is the turning around spot. But the trail continues from here making an insanely steep drop of more than 4300 feet in 3.6 miles to the Dosewallips River Road. It’s brushy in spots and easy to lose along the ridge. Otherwise it’s in decent shape down steep slopes and through old growth and past a small waterfall at Gamm Creek.

f you can arrange a car shuttle consider hiking out this route. There are some good views down to the Dosewallips River valley and out to Hood Canal during the initial descent if you want to just wander a little way down the trail. Otherwise start heading back to the cool forests of South Fork Tunnel Creek on the much more agreeable trail back to your start.

The details

Land Agency Contact: Olympic National Forest, Hood Canal Ranger District, Quilcene, (360) 765-2200,fs.usda.gov/olympic

Recommended Guidebook: Day Hiking Olympic Peninsula 2nd edition (Romano, Mountaineers Books)

Trailhead directions: From Shelton follow US 101 north for 50.5 miles. (From Quilcene, drive US 101 south for 1.5 miles). Turn left (west) onto Penny Creek Rd. After 1.5 miles bear left onto Big Quilcene River Rd (Forest Rd 27); which eventually becomes paved. At 3.0 miles bear left onto graveled FR 2740 and follow for 6.9 miles

Hamma Hamma's Living Legacy Trail

Take a leisurely hike back into time on this delightful trail along the Hamma Hamma River to the historic Hamma Hamma Cabin.

By Craig Romano, feature columnist

Craig Romano, is an author of more than twenty hiking guidebooks including the bestselling Day Hiking Olympic Peninsula 2nd Edition (Mountaineers Books), which includes detailed descriptions for 136 hikes throughout the Olympic Peninsula. Visit CraigRomano.com for more information.

Take a leisurely hike back into time on this delightful trail along the Hamma Hamma River to the historic Hamma Hamma Cabin. Constructed by the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC), the cabin was used as a guard station in Olympic National Forest. Today it stands as a testament to the craftsmanship and hard work of the CCC. Learn more about “Roosevelt’s Tree Army” and their legacy on this family friendly interpretive trail.

Photo: Craig Romano

In April of 1933 in the midst of the Great Depression, newly inaugurated president Franklin D Roosevelt established the CCC through an executive order. Roosevelt’s aim was more than just putting young men to work and allowing them to provide for their families.

"Roosevelt strongly believed in the spiritual and physical values of working in nature, and in the importance of conservation of our natural resources for the nation’s health and prosperity."

At its height in 1935, more than 500,000 young men were stationed in more than 2900 CCC camps in every state as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. At the program’s close in 1942, more than 3 million men (nearly 5% of the country’s male population) had served in the CCC. This trail sheds some light on what life was like for these men during their time in the Corp—and highlight some of their achievements and legacy.

Photo: Craig Romano

Among their many projects, CCC recruits were responsible for building vast amounts of infrastructure within parks and forests throughout the country—including both the Olympic National Park and Forest.

They also fought fires, reforested large tracts of land and worked on flood control projects. There were camps established right within Olympic National Park and Olympic National Forest, including one in the nearby Staircase Region. Nearby Twanoh State Park on Hood Canal also was the site of a large CCC camp.

Hit the Trail

Start your hike east on a wide and level path through a riparian forest of large mossy maples and speckled barked alders. The first quarter mile of this recently refurbished trail is ADA compliant. While this trail emphasizes the historic role the CCC played in this corner of Olympic National Forest, there is plenty of natural beauty to be enjoyed long the way as well. It is the only trail (albeit just for a short stretch) that runs along the Hamma Hamma River.

Photo: Craig Romano

The river’s name come from the Twana (whose ancestral lands included much of the Hood Canal region) word Hab’hab, which refers to a reed along the river’s banks. The name means big stink, or literally stinky, stinky in reference to the aroma the reeds emitted. The trail hugs a bank above the river allowing for some excellent views of the pretty waterway.

Photo: Craig Romano

Stop and look for dippers—robin sized birds that feed on aquatic insects and nest along the shorelines of rushing water. In spring look for Harlequin ducks returning from the Salish Sea. One of the prettiest sea ducks, they build hidden nests along rapid moving creeks and rivers.

The trail climbs a small bluff granting an excellent view of the pretty waterway, before leaving the river for forest. At 0.5 mile the trail turns north to cross Forest Road 25. Now walk along cascading Watson Creek climbing about 100 feet to a wooden bench on a perch overlooking the creek. It’s a great spot to sit and enjoy the sound of nature’s water music. By late spring nesting thrushes and other songbirds add a wide range of melodies.

The trail now turns west to soon reach the historic Hamma Hamma Guard Station. Built by the CCC from 1936 to 1937, it was used for administrative purposes for forest fire and trail crews. Today this eloquently rustic structure with its hexagonal bay window can be rented out for an overnight stay recreation.gov. Please respect the privacy of any guests staying at the cabin by not walking on the grounds. Otherwise wander around the structure. Note the landscaping too, especially the rhododendrons which will be in bloom come May.

Photo: Craig Romano

After admiring the historic structure continue west on the loop crossing a small creek and traversing a grove of mature second growth firs. The way then descends into a ravine before re-crossing FR 25. Continue hiking passing some big beautiful old trees before reaching the campground loop road near campsite no. 6. Now turn right and walk the loop road a short distance back to your start closing your loop hike at 1.8 miles. Reflect on some of the achievements of the Corp including the thousands of miles of trails they built, more than 3400 fire towers constructed, nearly 3 billion trees planted, and the development of amenities and infrastructure in more than 800 parks across the nation. Many of their works are still standing and in use in Olympic National Park and Olympic National Forest as well as at several nearby state parks. The Corp’s legacy continues to live on for the next generation of outdoorsmen and women.

Getting Here

First .25 mile ADA; Leave No Trace Principles

Land Agency Contact: Olympic National Forest, Hood Canal Ranger District, www.fs.usda.gov/olympic

Recommended Map: Green Trails Olympic Mountains East 168S

Trailhead directions: From Hoodsport travel north on US 101 north for 13.7 miles turning left at milepost 318 turn onto FR 25 (Hamma Hamma River Road). Then continue west for 6.0 miles turning left into the Hamma Hamma Campground. Proceed for 0.1 mile to trailhead located near site no. 12.

Trailhead facilities: campsites (fee), privy

April Showers Bring Spring Flowers

Although the Pacific Northwest is known for its temperate rainforests accompanied by an abundant amount of green, with April warmth, we can start to look forward to the colorful relief offered by the return of the native flowers around the Canal and South Puget Sound area.

Although the Pacific Northwest is known for its temperate rainforests accompanied by an abundant amount of green, with spring’s warmth, we can start to look forward to the colorful relief offered by the return of the native flowers around the Canal and South Puget Sound area.

April to June is the best time of year for finding the delicate jewel tones out here on the wet coast. Whilst domesticated daffodils and tulips will always be celebrated markers of Spring, our native plants are often forgotten gems of the forests understory. As the days get longer and the weather gets warmer, take a ramble down one of Mason County’s forested walks, like Twanoh State Park Trail or for a more adventurous alpine hike, with spectacular views and unique flora, try Mount Ellinor Trail.

Keep your eyes peeled for the first nodding, purple blossoms of Henderson's Shooting Star (Dodecatheon hendersonii) and the showy, pinky-purple blooms of our local variety of Rhododendron (Rhododendron macrophyllum).

The Pacific Rhododendron is Washington’s State flower and is found in drier parts of the Hood Canal in the understory of coniferous forests.

There are nearly 30 varieties of Rhododendrons native to North America. The Pacific Rhododendron is Washington’s State flower and is found in drier parts of the Hood Canal in the understory of coniferous forests. Pacific Rhododendron can also be seen in partly sunny, open areas, such as along roads. The Pacific Rhododendrons and also Goat's Beard (Aruncus dioicus) can be found in proliference along the winding, scenic 101 Highway following Hood Canal. For an especially spectactular showing of the native rhodendrons, head up to the scenic outlook on Mount Walker.

Pink Fawn Lily

In sunnier, damper areas, near streams, look for the bright pink flowers of Pink Fawn Lily (Erythronium revolutum) or the iconic, if not slightly smelly, “West Coast Daffodil”— Skunk Cabbage (Fritillaria lanceolata). Also in sightly shady, waterside spots, look for carpets of pink Bleeding Heart (Dicentra formosa)— a more delicate version of our domestic variety. Try the Kamilche Kennedy Creek Trail for these humid loving flowers.

Orange Honeysuckle

As the weather gets warmer (from May to June) search in the partly shady area of the woods for the trailing tender beauty of Orange Honeysuckle (Lonicera ciliosa), and the yellow blossoms of Tall Oregon Grape (Mahonia aquifolium). The delicate, orange-red blooms of Red Columbine (Aquilegia formosa) also emerge during this time.

Camas was actively cultivated and traded between first peoples throughout the Northwest who would harvest the bulbs in the early spring and roast them in pit cooks.

Other blossoms to look for in the late spring are the azure, crocus-like flowers of the Common Camas (Camassia quamash). Found in full sunlight in open places, such as fields, parklands, the bulbs from the Camas were an important part of the diet of Native Americans. Known as k’a’w˜up to the Skokomish and sxa’dzaêb by the Squaxin, this bulbous flower was actively cultivated and traded between Nations throughout the Pacific Northwest who would harvest the bulbs in the early spring and roast them in pit cooks.

On one of those calm days when you believe it might just be summer here early, pack a lunch and hop in the boat and travel to Hope Island Marine State Park. Here you will be greeted by lovely trails and beautiful naturalized gardens with a mix of introduced and native species.

Red Paintbrush

Once settled as a farm, Hope Island has historic fruit trees mixed in with native camas, honeysuckle and the elegant red, trunks of Madrone (Arbutus menziesii). An unusual looking plant found along sun-facing, beach banks is the Red Paintbrush (Castilleja miniata), whose tiny green flowers are hidden in bright red leaves that give the appearance of a brush dipped in red paint. Since most of these species are protected against picking or transplanting, remember to keep your enjoyment to viewing.

You can take as many photographs as you like, but refrain from taking bouquets and let the native flowers thrive.

If casual enjoyment of our native plants is what your after, the Washington Native Plant Society has plant identification resources online and there are plenty of guide books to help. Pojar and Mackinnon’s Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast (2014) and Nancy J. Turner’s Food Plants of Coastal First Peoples (1995) offer excellent information, photographs and tidbits that add color to an already polychromatic subject. Happy hunting!

Hood Canal "Glamping"

If your idea of a camping excursion is freeze dried food and dry shampoo – and luxury to you is a bed of moss under your sleep sack or a solar-powered lamp – "glamping" may not hold much interest for you. Glamping or "glamor-camping" as the name suggest, goes WAY beyond the coleman stove and solar shower upgrade. If you crave a star-studded forest canopy while enjoying gourmet camp cuisine and all the comforts of home – bed, pillows, duvet, light switches– glamping may be a great compromise to get outdoors!

If your idea of a camping excursion is freeze dried food and dry shampoo – and luxury to you is a bed of moss under your sleep sack or a solar-powered lamp – "glamping" may not hold much interest for you. Glamping or "glamor-camping" as the name suggest, goes WAY beyond the coleman stove and solar shower upgrade. If you crave a star-studded forest canopy while enjoying gourmet camp cuisine and all the comforts of home – bed, pillows, duvet, light switches– glamping may be a great compromise to get outdoors!

Header Image credit: Poppi Photo

One of the best thing about "camping" is relaxing with a final roasted marshmallow and a steaming mug of hot chocolate. Wrapped in a cozy blanket, the tall trees keep you close in the inky darkness beyond the glow of the fire. Far from the glow and clatter of the city, the sky displays a covering of unrealistically bright stars. Good conversation and the people you love surrounding you. Who wants to consider the uncomfortable night ahead? Rocks in your lumbar. Slick "high performance" sleeping cocoons that tangle and suffocate. Never mind the 3:00 AM Call of Nature. Stumbling through the dark stubbing toes and tripping over roots.

Trailer camping is technically considered in the "glamping" category, above the waterfront view and tall trees at Twanoh State Park, Hood Canal definitely set the standards high.

Enter glamping. A purist would say if you want the experience of camping you need to embrace the whole experience, not cherry-pick the best parts. Galen Patterson, a journalist with Arcadia Weekly, remarks in a recent article, "in its luxury, comfortable camping (glamping) loses what makes the experience worth the discomfort in the first place." He goes on to say that, "instead of connecting with nature and all of its uncomfortable facets, people are bringing the comforts of home with them, and, in doing so, are sapping the spirit of what it means to connect to the outdoors." Patterson advocates that through discomfort and deprivation, he "finds appreciation and, with it, follows a new zest for life."

Hmmmm. So unless you are suffering you will not appreciate the wilderness? Good riddance. Rough camping has its place – when space is limited in your kayak or you are pack/wilderness camping and every extra ounce needs to be "weighed" in necessity. However, if you can enhance the joy of spending time outdoors by increasing the comfort level – there is no shame in that!

There are plenty of definitions of glamping. Some feel that cooking on anything beyond an open campfire is glamping. Others consider having cell service a mark of glamor camping. Perhaps it's sleeping in a bed off the ground, in a cabin or RV. Whatever the case, glamping is a more glamorous spin on camping and it is bringing a whole new level of interest to the camping scene. Love it or hate it, glamping is a thriving trend that continues to grow.

Give it A Try....

Belfair State Park is a 65 acre, year-round camping park on 3,720 feet of saltwater at the southern end of Hood Canal. It is noted for its saltwater tide flats, wetlands with wind-blown grasses and pleasant beach walking and swimming. Cabins sleep five and are furnished with tables and chairs. Outside is a picnic table and fire pit. Bathrooms and showers are nearby. All cabins are heated, but visitors should take along blankets and warm clothing as evenings can be cool. Belfair cabin rates range from $40 (off-season) to $69(peak). Reserve

Dosewallips State Park offers canvas platform tents for rent. Situated in a maple forest near the Dosewallips River, the tent sleeps up to five people. Made of white canvas on wooden platforms, they are light inside, even on cloudy days. Each tent has three bunks, a futon, lights, table and heater. Outside is a deck, picnic table, fire grill and utility hookup. Bathrooms nearby. All platform tents are heated but campers must bring their own bed linens. Cabins at Dosewallips are situated among evergreen trees looking towards the Olympic Mountains. Each cabin features a covered porch, electric heat, lights and locking doors. Bathrooms are nearby. Tent and cabin rates range from $40 (off-season) to $69 (peak). Reserve

Hamma Hamma cabin is available through the Olympic National Forest

The Hamma Hamma Cabin in the Olympic National Forest is a historic cabin that offers guests a tranquil setting. Formerly a guard station, the cabin was built in 1937 by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The site is nominated to the National Register of Historic Places for the skill and craftsmanship that went into its construction and architecture. The cabin is open year-round. Accommodating up to six guests, the single-story cabin features a living room with a hexagonal bay window overlooking the Hamma Hamma River drainage. There are two bedrooms, one with a double bed and one with bunk beds. The bathroom has a flush toilet. The cabin is equipped with a propane heater and propane lights. An outdoor picnic table, fire ring and pedestal barbecue grill are available for cooking and campfires. Guests provide their own bedding, linens, towels, dish soap, matches, first aid kit, toilet paper and garbage bags. Reserve

Located in Union, the Pebble Beach Cottage has two beds, one bathroom and can sleep up to 5-6 guests. Sitting approx. 75 feet from the water it has a beautiful view of the canal, and surrounded by a cedar forest. This carriage house is a bed and breakfast style stay with a part-time caretaker on sight. Guests enjoy privacy of a vacation home, (as this property is completely separate from the main house), yet access to concierge services. (Rate $195) Reserve at glampinghub.com.

The Tahuya Adventure Resort is located in the heart of the Tahuya Forest past Belfair. Featuring campsites with hook-ups and luxury platform tents, this is glamping heaven! The Log Cabin tent features a king size log bed, bunk-beds, oversized chairs and tables, pellet stove, carpet, refrigerator, microwave, and a coffee pot. Each site has an outdoor picnic table and fire ring or you are welcome to use their covered kitchen. (Rate $500/2 nights) Reserve at tahuyaresort.com.

The ultimate "glamping" experience can be provided by Hood Canal Events located in Union, WA. For a fee they can arrange the perfect getaway for you and your signifigant other – or the whole family. From setting up the camp & tent (pictured above) in a spectacular location, arranging tours, hikes or kayaking expeditions, to chef prepared gourmet meals in your camp – Jeff and Kerry can take care of it all for you. Call them directly at (360) 710-7452 or visit hoodcanalevents.org. Photo Poppi Photography

Hood Canal Events, based in Union, can provide unique glamping experiences. Offering everything from a Hood Canal beach glamor picnic (great for intimate gatherings, family picnicking, lounging, or celebrations) to a fully catered overnight trip, they can arrange special requests your group may have. Hood Canal Event's packages include furnishings, amenities, activities (kayaking to mushroom foraging or live music) and a chef for locally prepared food and beverages. Overnight glamping packages are available. For information on rates or customizing an experience, call (360) 710-7452, or visit hoodcanalevents.org.

Above are just a few ways you can elevate your "glamping" experience on Hood Canal. There is no wrong way to do it. If you prefer backcountry camping, with your home on your back and no connection to civilization, the Olympic National Park has that too. Camp for days and never see another soul in the backcountry areas. Talk about "finding appreciation."

If camping or glamping is not your thing thats cool too. Hood Canal and South Puget Sound have wonderful guest lodging and rentals right on the beach – with power and flush toilets. Visit explorehoodcanal.com/lodging for a complete list that is updated weekly.

Whatever you choose, just get out there and create some great memories – stubbed toes or not!

Don’t let the chilly water discourage you…dive in!

Just below the surface of the waters of the Hood Canal, a whole new world exists waiting to be explored. It is carpeted with sponges and seaweed, populated by wolf eels and octopus and visited by the occasional seal and even (rarely) a six-gilled shark. Although the cold water of the Pacific is daunting, the variety of marine life it holds is well worth the chilly SCUBA dive.

Just below the surface of the waters of the Hood Canal, a whole new world exists waiting to be explored. It is carpeted with sponges and seaweed, populated by wolf eels and octopus and visited by the occasional seal and even (rarely) a six-gilled shark. Although the cold water of the Pacific is daunting, the variety of marine life it holds is well worth the chilly SCUBA dive.

With its comparably slower currents (to the rest of Puget Sound), the Hood Canal offers many opportunities for rewarding shore dives and live boat dives of various experience levels. Diving is not just for the summer time, the winter and early spring offer excellent opportunities because the cooler weather means clearer visibility (rain run off notwithstanding).

We have coalesced a list of some of the top dive sites of the Hood Canal as recorded by excellent books such as Betty Pratt-Johnson’s 141 Dives in the Protected Waters of Washington and British Columbia (1977) and Stephen Fischnaller’s Northwest Shore Dives (2000), as well as diver’s blog reviews, such as Scott Boyd at Emerald Sea Scuba and Nicolle Prat at Pacific Northwest Scuba.

#1. Flag Pole Point

East and West

Outside of Lilliwaup, just to the South of Mike’s Beach Resort is a dive site more comfortably accessed by boat (but you can free swim to it also). Called “the knuckle” this dive site consists of a series of rock formations, rising like a mini range of mountains from the ocean floor. Because this formation is farther out and more exposed to currents, this site usually has excellent visibility and there are lots to see. Lingcod lay their eggs at this protected site, and there are resident wolf eel and octopus populations. Since the rise of “the knuckles” is so rapid, the site can be difficult to locate— check the dive blogs for more information and ask your local dive shop.

#2. Potlatch Park -

While the diving at Potlatch is less dramatic than the site above , if you are just getting your flippers wet, this is a great place to start out. This shore diving spot is easy to get to, has showers to wash off gear, and it provides opportunities to get comfortable with your equipment and practice techniques.

#3. Scenic Beach State Park –

Like Potlatch, this site is accessible from the beach and it is rewarding for all experience levels. There are plenty of marine life to observe on this sandy-cobble beach, which shifts after 15 ft into a large eelgrass bed, likewise teaming with all the sea creatures that are heir to this environment.

#4. Octopus Hole –

Although parking for this site is limited, this wall site is easy to access from shore and gratifying for all experience levels, but it is a popular spot! It is recommended you brings a flashlight to see the friendly octopuses and wolf eels. Remember this is a protected site, so no harvesting or disturbing the site (and no taking of the glass bottles that octopuses like to hide in).

#5. Sund Rock Marine Preserve

Easy beach access to this site is available through Hoodsport ’N Dive for $20 per diver. This is an iconic dive spot of the area —Hoodsport ’N Dive even offers diving classes at this site. From the beach you swim out through eelgrass environs filled with perch, crabs and other types of sea life. When you reach the Rock you are greeted by wolf eels, octopuses, sea stars, lingcod and other bottom fish. As it is a marine preserve it is closed to harvesting and fishing — so no spear guns!

Twanoh State Park offers easy access to the water.

#6. Twanoh State Park –

This full service park, has a gentle current, which gives divers the freedom to dive whenever— independent of slack tides. You will find a large eelgrass bed filled with interesting fish, such as tube-snouts, black eye gobies and sticklebacks. After about 40 foot depth you can find tube-dwelling anemones. These anemones are entertaining to watch as they feed with their long graceful tentacles. Use a dive flag and submerge when you pass the roped swimming area (and stay submerged and deep to avoid any boat traffic).

#7. The east side of Hood Canal Bridge

This is a more intermediate dive. Leaving from the park at Salsbury Point heading toward the Hood Canal Bridge, this shore dive requires you time your swim out to the dive area right before the beginning of slack tide, so that the current pulls you out to the bridge, then you can save your energy for the swim back. On your swim out to the bridge you pass through eelgrass beds, which are teeming with perch, soles, shiners and other sea creatures. When you reach the concrete bridge supports you are greeted by a fantastic display of plumose anemones and many different types of nudibranchs. Be careful of boat traffic and pace yourself for the long swim to and from the bridge.

For more information on scuba opportunities in the Hood Canal area, visit our scuba things to do page!